Why Lebanon’s government resigned and who will rule now

Prime Minister Hassan Diab condemns ‘corruption network’ as he steps down following Beirut explosion

The entire government of Lebanon has resigned following a week of widespread protests in the wake of the deadly chemical explosion in Beirut last week.

In a brief televised speech on Monday night, Prime Minister Hassan Diab said he was taking “a step back” so that he can stand with the people “and fight the battle for change alongside them”. The massive blast that tore through the capital last Tuesday, killing at least 200 people, was a result of a “corruption network” that is “bigger than the state”, he claimed.

The mass resignation followed “a weekend of angry, violent anti-establishment protests in which 728 people were wounded and one police officer killed amid a heavy crackdown by security forces”, reports Al Jazeera.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why has the government resigned?

Even before last week’s explosion, Lebanon was gripped by a crippling political and economic crisis, which has been exacerbated by the ongoing coronavirus pandemic.

As of the start of this year, the country’s public debt-to-gross domestic product was the third-highest in the world, unemployment stood at 25% and nearly a third of the population was living below the poverty line.

“At the same time, people were getting increasingly angry and frustrated about the government's failure to provide even basic services,” the BBC reports. “They were having to deal with daily power cuts, a lack of safe drinking water, limited public healthcare, and some of the world's worst internet connections.”

This anger bubbled over following the explosion, amid reports that the blast was the result of the improper storage of almost 3,000 tons of highly explosive ammonium nitrate fertiliser that had been left in a warehouse in Beirut’s port area after being confiscated from a ship impounded in 2013.

Lebanese security officials warned Prime Minister Diab and President Michel Aoun in July that the chemical stockpile “could destroy the capital if it exploded”, according to documents seen by Reuters.

Furious demonstrators who took to the streets this weekend “blamed the disaster squarely on corruption and neglect from the country’s long-entrenched ruling class”, Sky News reports.

By Monday, three cabinet ministers had quit, along with seven members of parliament, prompting Diab - who only took power in January this year - to follow suit.

What did Diab say?

In what CNN calls an “impassioned” speech, Diab “berated Lebanon's ruling political elite” for allegedly fostering corruption and neglect.

Diab said his government had “gone to great lengths to lay out a road map to save the country” from its economic woes, but claimed that “a very thick and thorny wall separates us from change - a wall fortified by a class that is resorting to all dirty methods in order to resist and preserve its gains”.

“They knew that we pose a threat to them, and that the success of this government means a real change in this long-ruling class whose corruption has asphyxiated the country,” he added. “Today, we follow the will of the people in their demand to hold accountable those responsible for the disaster that has been in hiding for seven years, and their desire for real change.”

What next?

President Aoun yesterday asked the government to stay on in a caretaker capacity until a new cabinet is formed.

However, while foreign observers may see the impending change in leadership as a game-changing development for Lebanese society, “the end of this government does not necessarily mean an end to the anger”, says the BBC.

“It is unlikely to be a smooth or quick process due to the country's complex political system. Power in Lebanon is shared between leaders representing the country’s different religious groups,” explains the broadcaster, which notes that “last year’s protests led to the formation of the government which has now been forced to step down over the same accusations of corruption”.

Rima Majed, a professor of sociology at the American University of Beirut, fears that Lebanon is facing a bleak future.

“This is probably the most dangerous moment in the history of this country. Unfortunately, the options we have today are very grim,” he told Sky News’ Beirut correspondent Alex Rossi.

“If there isn’t a serious will from the international community to create serious structural change in this country, we are going towards civil war. There is no alternative. It’s very unfortunate to say that in this country, we don’t believe there is rock bottom any more.”

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Ukraine-Russia: is peace deal possible after Easter truce?

Ukraine-Russia: is peace deal possible after Easter truce?Today's Big Question 'Decisive week' will tell if Putin's surprise move was cynical PR stunt or genuine step towards ending war

By The Week UK

-

The bougie foods causing international shortages

The bougie foods causing international shortagesIn the Spotlight Pistachios join avocados and matcha on list of social media-driven crazes that put strain on supply chains and environment

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK

-

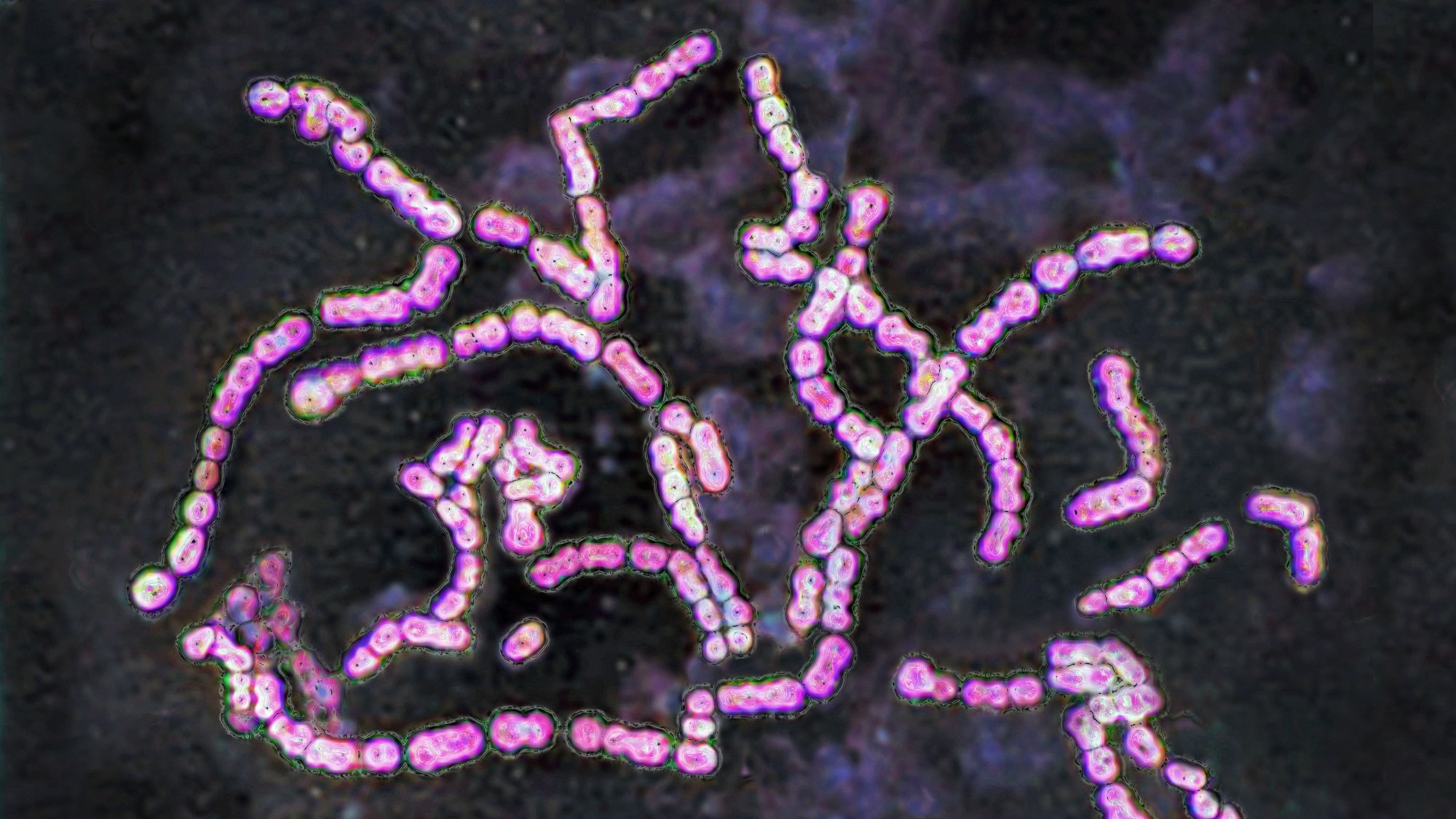

Strep infections are rising in the US

Strep infections are rising in the USUnder the radar The cases have more than doubled in 10 years

By Devika Rao, The Week US

-

Why Russia removed the Taliban's terrorist designation

Why Russia removed the Taliban's terrorist designationThe Explainer Russia had designated the Taliban as a terrorist group over 20 years ago

By Justin Klawans, The Week US

-

Inside the Israel-Turkey geopolitical dance across Syria

Inside the Israel-Turkey geopolitical dance across SyriaTHE EXPLAINER As Syria struggles in the wake of the Assad regime's collapse, its neighbors are carefully coordinating to avoid potential military confrontations

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US

-

'Like a sound from hell': Serbia and sonic weapons

'Like a sound from hell': Serbia and sonic weaponsThe Explainer Half a million people sign petition alleging Serbian police used an illegal 'sound cannon' to disrupt anti-government protests

By Abby Wilson

-

The arrest of the Philippines' former president leaves the country's drug war in disarray

The arrest of the Philippines' former president leaves the country's drug war in disarrayIn the Spotlight Rodrigo Duterte was arrested by the ICC earlier this month

By Justin Klawans, The Week US

-

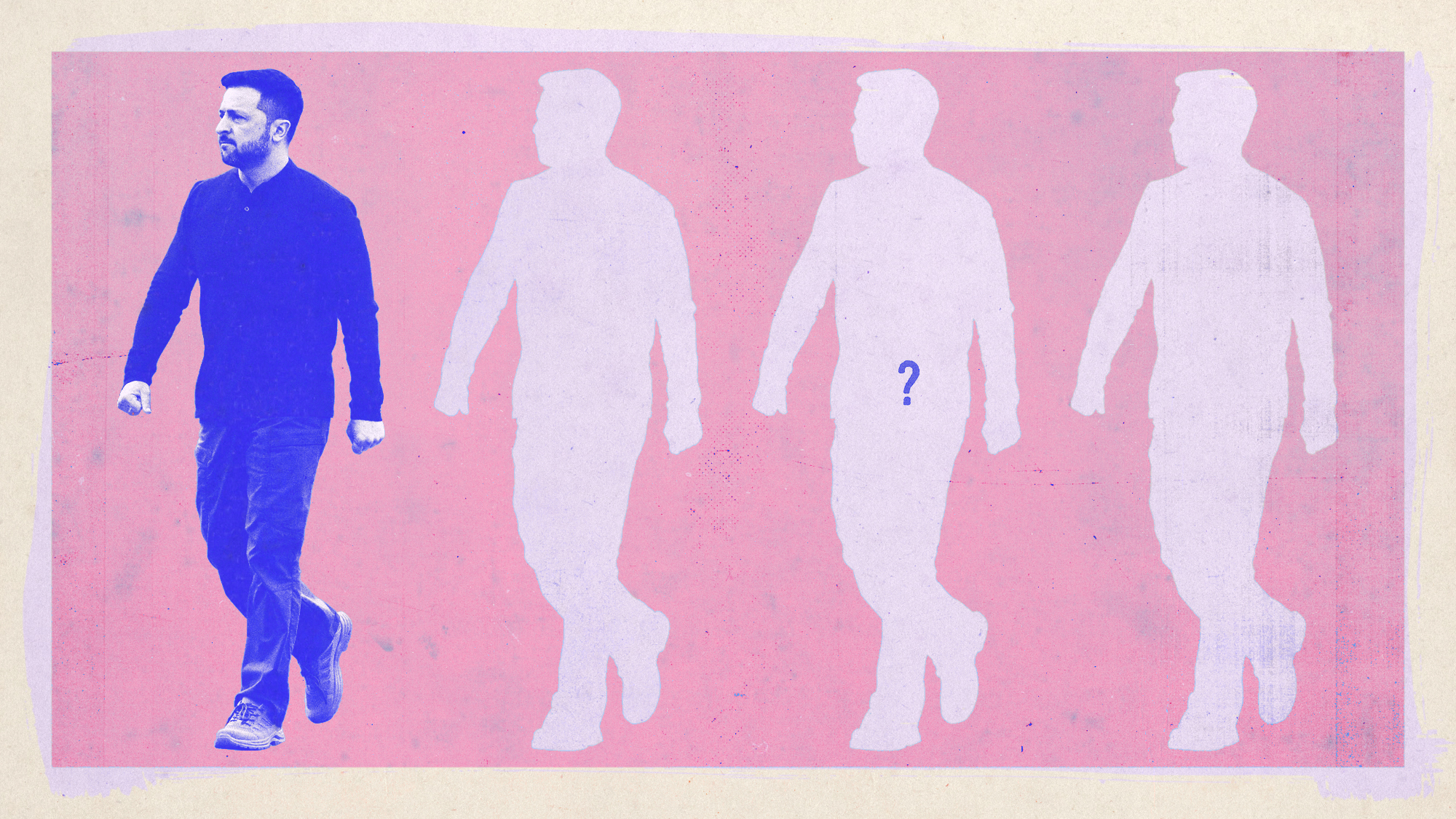

Ukrainian election: who could replace Zelenskyy?

Ukrainian election: who could replace Zelenskyy?The Explainer Donald Trump's 'dictator' jibe raises pressure on Ukraine to the polls while the country is under martial law

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK

-

Why Serbian protesters set off smoke bombs in parliament

Why Serbian protesters set off smoke bombs in parliamentTHE EXPLAINER Ongoing anti-corruption protests erupted into full view this week as Serbian protesters threw the country's legislature into chaos

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US

-

Who is the Hat Man? 'Shadow people' and sleep paralysis

Who is the Hat Man? 'Shadow people' and sleep paralysisIn Depth 'Sleep demons' have plagued our dreams throughout the centuries, but the explanation could be medical

By The Week Staff

-

Lebanon selects president after 2-year impasse

Lebanon selects president after 2-year impasseSpeed Read The country's parliament elected Gen. Joseph Aoun as its next leader

By Peter Weber, The Week US